Had the attack been any later, there would have been around 100 platform-sleepers there, many of whom make their living as “rag-pickers”, sifting through the rubbish left by commuters for materials they can sell for recycling.

Pappu said he was paid 150 rupees (£1.75) a day as a rag-picker at Mahim, and that dozens of boys and homeless young men did similar work at all the stations hit by the bombings. He was sure railway children were among the victims at those stations too, he said.

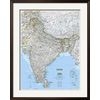

The children come from broken homes and large, poor families in India’s most desperate states such as Bihar and Assam. They aim for big, prosperous — and to these children, glamorous — cities such as Delhi, Bangalore and especially Mumbai, India’s city of dreams.

But with little money, no family or friends, few get further than the railway station they arrive at, with its ready network of children and the possibility of scratching a living of sorts.

According to Abdul Malik, who left his home in Bihar on India’s eastern flank to find a “better life”, station “coolies”, the red-jacketed porters who hustle for tips along the platforms, were also badly hit by the bombs.

Abdul Malik, Mohammed Hussein, and Pappu are among the many thousands of homeless children who live in and around the stations of India’s sprawling rail network.

In Delhi, 2,000 children are believed to make their living along the platforms. Along with western volunteers, they have formed a charity offering tours of the “other side of the tracks” for 200 rupees. It ploughs the profits into education and training for the children.

They show tourists the “safe” nooks and crannies where they sleep, the rag-picking middle men who buy the discarded rubbish that the children collect, and offer talks by street children on the violence, abuse and camaraderie they say are all part of their railway experience.

Mumbai’s railway children are not so organised. Their suffering has yet to feature on any tourist trail. Their stories have been overlooked since last Tuesday in the broader and better articulated tragedies of those whose friends and families searched the city for them.

One family had searched every mortuary and hospital in the city, and had seen almost every victim without finding their son. They discovered later that he had died in one of the hospitals they had visited.

“If we’d known we could have saved him, we could have taken him to a private hospital or held his hand as he passed away,” one relative said. The city’s hospitals have been posting photographs of the dead to speed identification.

Stars from Bollywood held a candlelit prayer vigil for the victims while police mounted two equally important operations — one to find the culprits, the other to prevent communal riots.

Arup Patnaik, a police commissioner, said his officers were visiting community leaders and patrolling volatile districts. “We’re hoping for the best, but preparing for the worst,” he said.

The search for the culprits has focused on a little-known group, the Students Islamic Movement of India. It began as a Muslim empowerment movement in the 1970s but took a militant turn in the early 1990s and now supports Al-Qaeda.

Its founder, Mohammad A Siddiqi, is a journalism professor in America. Last week he said the group had turned militant after he left it. “Not in my wildest dreams did I think it would become an extremist fundamentalist group,” he said.

THE explosions that ripped through the first-class carriages of seven Mumbai commuter trains last week, killing nearly 200 people, were not meant for 14-year-old Pappu and his friends Malik and Mohammad.

THE explosions that ripped through the first-class carriages of seven Mumbai commuter trains last week, killing nearly 200 people, were not meant for 14-year-old Pappu and his friends Malik and Mohammad.![]() Facebook |

Facebook |

The comments are closed.